What You Need to Know About the Spotted Lanternfly

Learn how to identify, manage, and prevent one of the fastest-spreading invasive insects in the U.S.

North Carolina gardeners may have heard of the notorious spotted lanternfly by now. This bold and striking insect has already been spotted in four counties in northwest North Carolina, and there’s little stopping it from spreading further south and east. It showed up in Pennsylvania in 2014 and is now established in 18 states. It’s one of the newest pest species to arrive from Asia, and one of the fastest spreading. It was brought here unintentionally courtesy of our relentless and continuous shipment of goods from around the world.

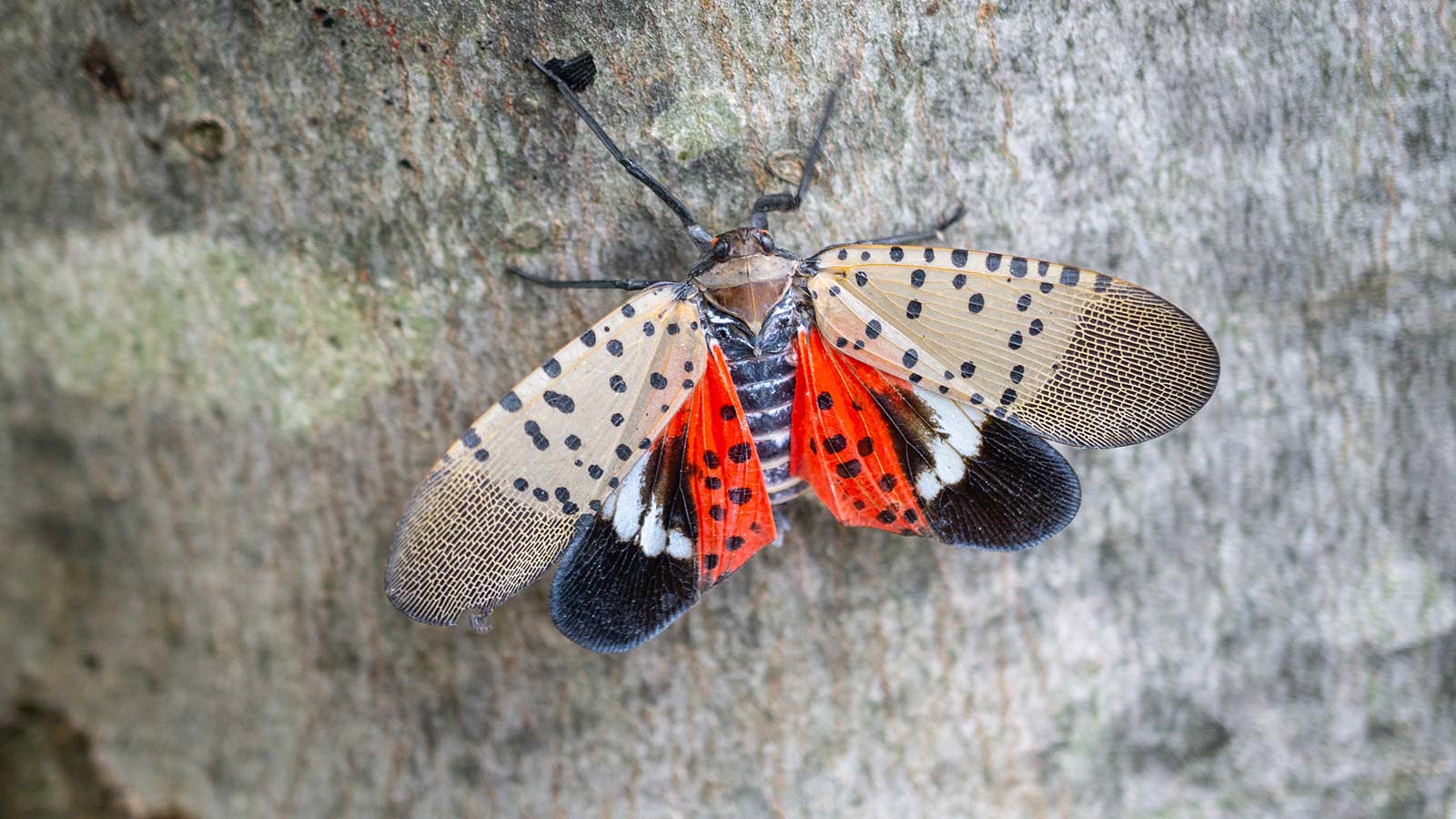

What Exactly Is This Beautiful Beast?

- Adult lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) are about an inch long and have a pair of pale pink wings with black spots tented over their bodies. The underwings are half black and white, with the inner half being blood-red with black spots.

- When their wings are spread, they resemble a moth. However, it’s neither a moth nor a fly – rather, it’s a true bug, more closely related to cicadas, leafhoppers, and planthoppers.

- More specifically, it’s a planthopper from a family that’s mostly tropical, although it has a close relative — a harmless, small planthopper that lives inconspicuously on native palmettos.

Why Is It Bad?

- The primary concern is that it is non-native and invasive, which allows it to thrive without its natural predators and reach populations larger than the ecosystem can handle.

- It feeds on plants in the same way all true bugs do—with piercing, sucking mouthparts that extract sap.

- Like many sap-sucking insects, they also secrete sticky honeydew, which turns black with sooty mold, creating a mess and challenging the plants they affect. Many gardeners recognize this because many aphids have a similar MO.

- They mainly target grapes, maples, tree-of-heaven, black walnut, hops, and fruit trees, but they aren’t too picky.

Will They Kill My Trees?

- Spotted lanternflies are very bad news in vineyards. Grape vines can be damaged so badly that they are killed or need to be removed.

- Fruit trees and ornamental trees can also be assaulted and damaged, especially if they are already stressed.

- Healthy trees, especially forest trees can be affected, but they will usually cope.

How Does It Live?

Remember learning about metamorphosis in grade school? Sort of? Recognizing the life stages is essential for identifying this bug.

- Like all true bugs, after the eggs hatch, the baby lanternflies called nymphs grow larger in 4 stages, moulting between each stage. They are glossy black with white spots until the last stage when they turn glossy red and black with white spots.

- Then, in the final 5th stage they develop wings and are adults, ready to reproduce.

- Like most members of their group they have powerful legs. The nymphs can use these powerful legs to jump up to 3 feet, and cat-like, they never fail to land on their feet.

- The eggs are laid on tree trunks and just about anything else at hand, such as cars, or really any vertical surface. They look like gray, mud-like patches about 1 inch long, often looking like dried smears of putty. Over time, the coating flakes, revealing rows of brown seed-like eggs.

- There is only one generation a year, so that’s a bit of a relief.

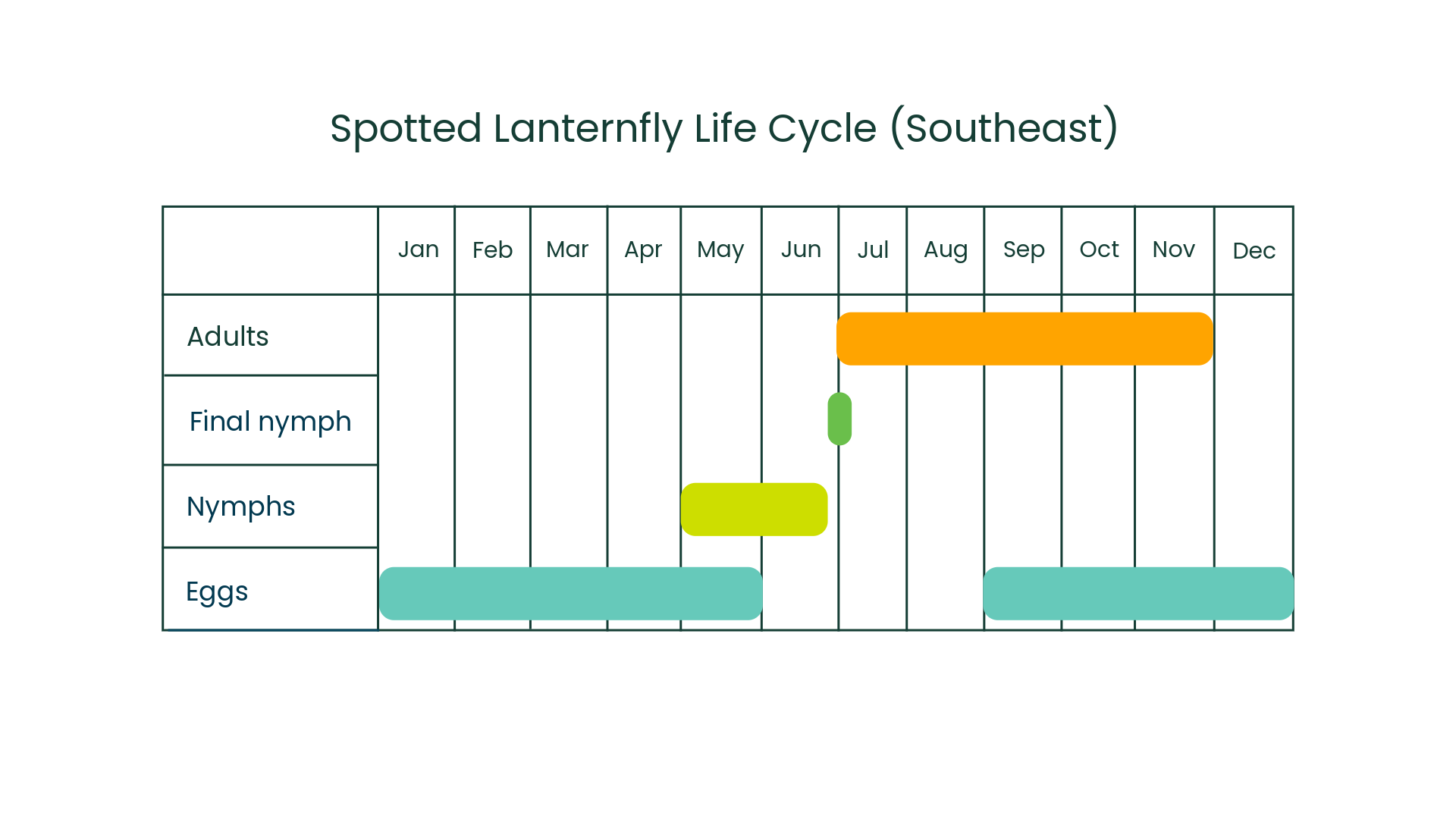

Here is a chart showing the lifecycle in the US southeast.

Cool Facts About Lanternflies

- Scientists are carefully considering whether introducing their natural predators from Asia (tiny non-stinging parasitic wasps) will be beneficial.

- Their preferred tree is the tree-of-heaven, an invasive non-native species, so that’s some good news.

- Rumors that this pest is attracted to power lines turned out to be true. Lanternflies don’t sing like cicadas to attract mates, but they communicate through vibrations that they can feel with their legs. Our power lines vibrate at 60Hz, which might disrupt their mating strategies—something to study.

- Researchers at Virginia Tech are training dogs to sniff out egg masses.

- Spotted lanternflies don’t bite or sting and pose no harm to humans or other animals.

Is There Anything I Can Do?

- Learn to recognize the life stages, especially the egg masses and destroy them as you find them.

- Give the scary predator bugs in your yard lots of grace. Spiders, wasps, hornets, ants, mantids and other predator insects will add lanternflies to their diets.

- If you have ducks and chickens, they happily gobble up lanternflies.

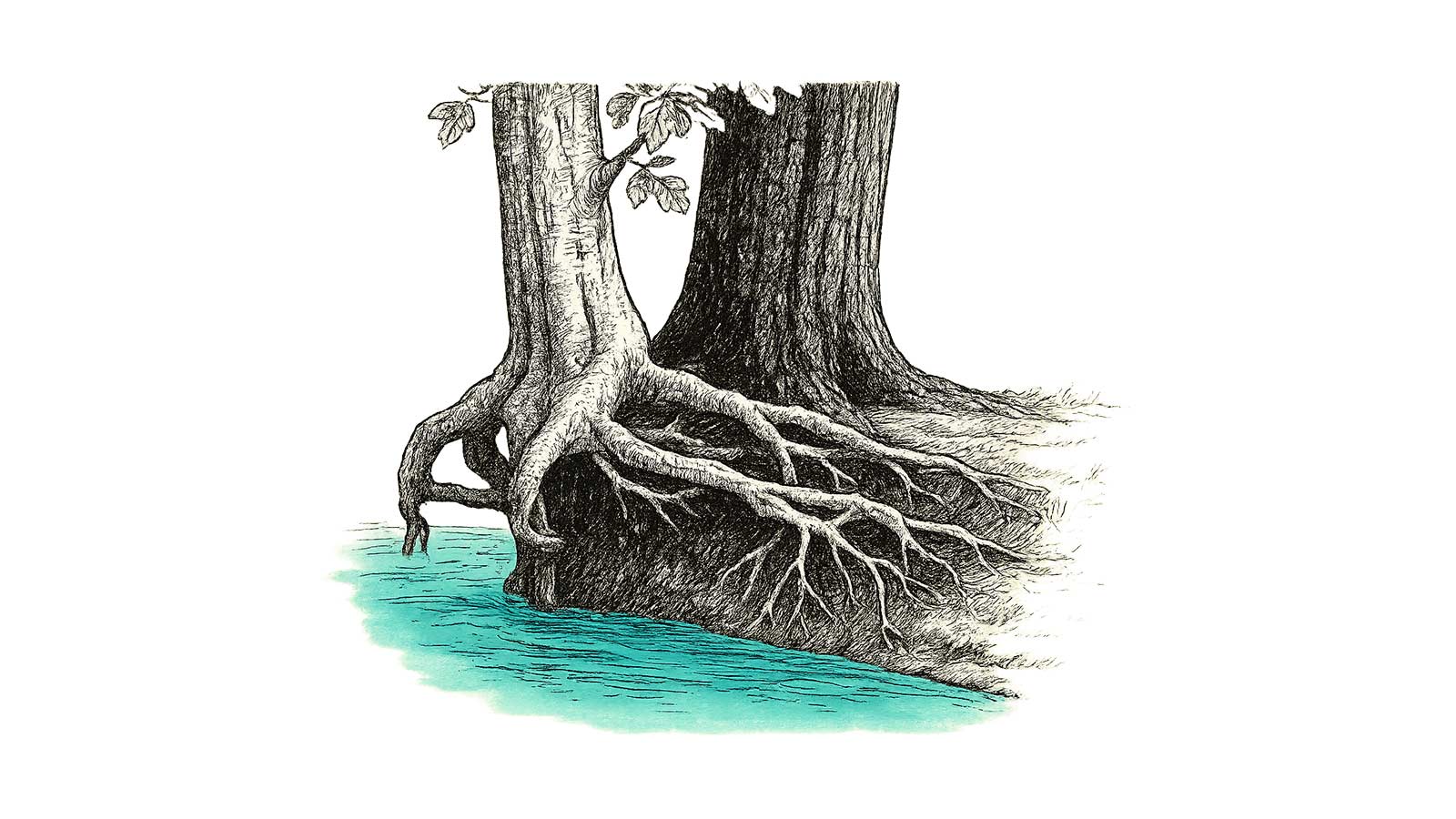

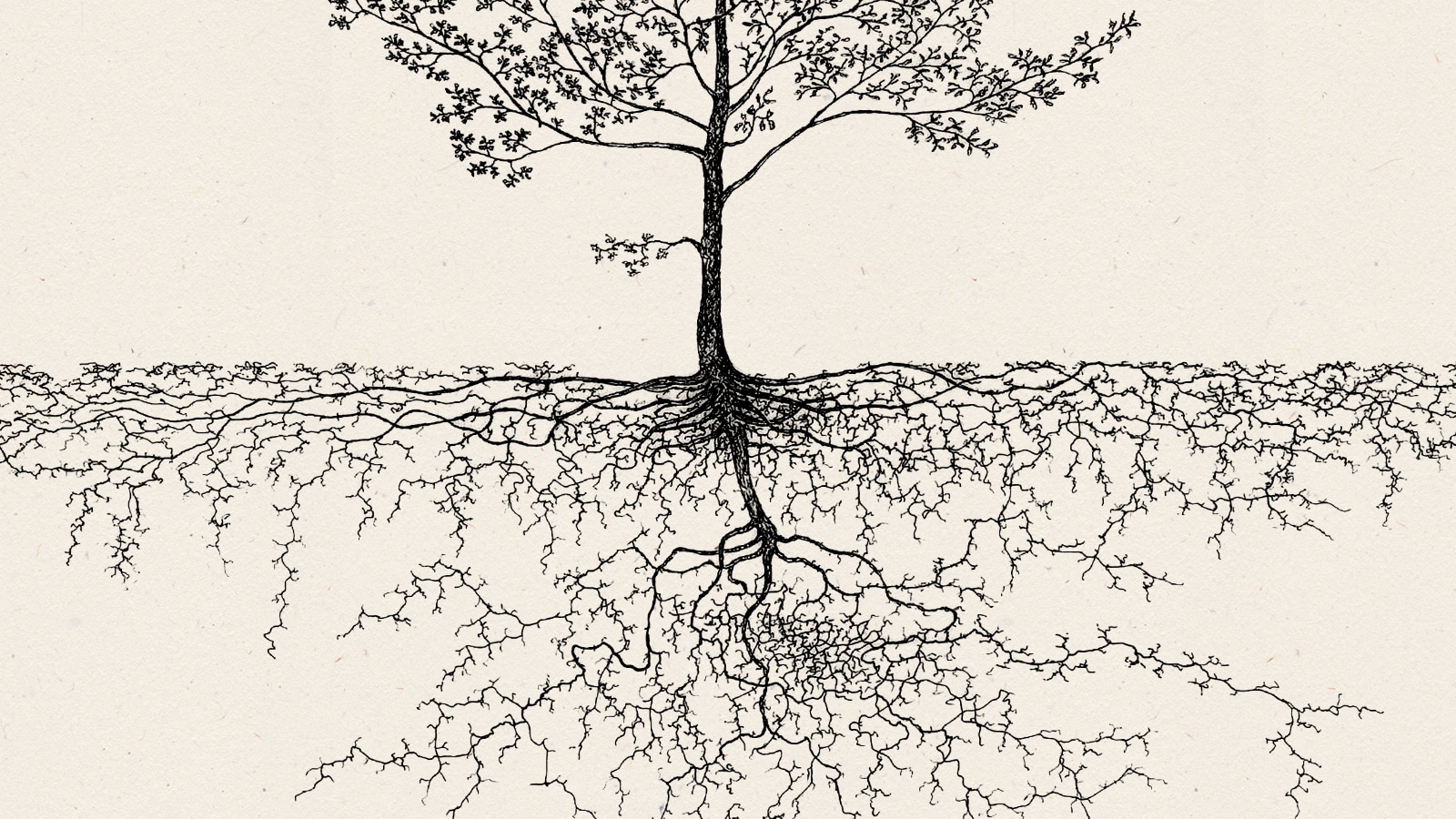

- Do everything you can to keep your fruit and ornamental trees healthy. That starts with the roots. Make sure your soil is in great shape. Contact one of our Treecologists to get a head start on keeping your trees well-fortified before the bugs arrive.