November 2025 Treecologist Tribune

Lessons From the Leaf Litter 🍂

In the South, winter feels more like a time to put your feet up for a solid snooze and a refreshing reset than the full-on hibernation of a northern winter. I felt like winter barged in like it owned the place last week, though, to remind me that it had arrived. 🥶

I learned a lot this last month, on my hands and knees, squinting through the leaf litter. Last month, if you remember, I was collecting hickory nuts. I’ve been really jazzed about seed collecting this fall, perhaps more than usual. One of the main things I’ve come to appreciate is that there’s so much to find if you know how to look. A hickory might knock on your skull to get attention, but the smaller tree seeds I was collecting this last couple of weeks needed a closer look.

Have you ever seen a beech nut? Spiky capsules contain two smooth triangular seeds.

And black gum—I like to call them tupelo—has fruit that looks a lot like blueberries.

Once you’ve found your tree of interest, drop down and dig through the leaves!

Weather Notes

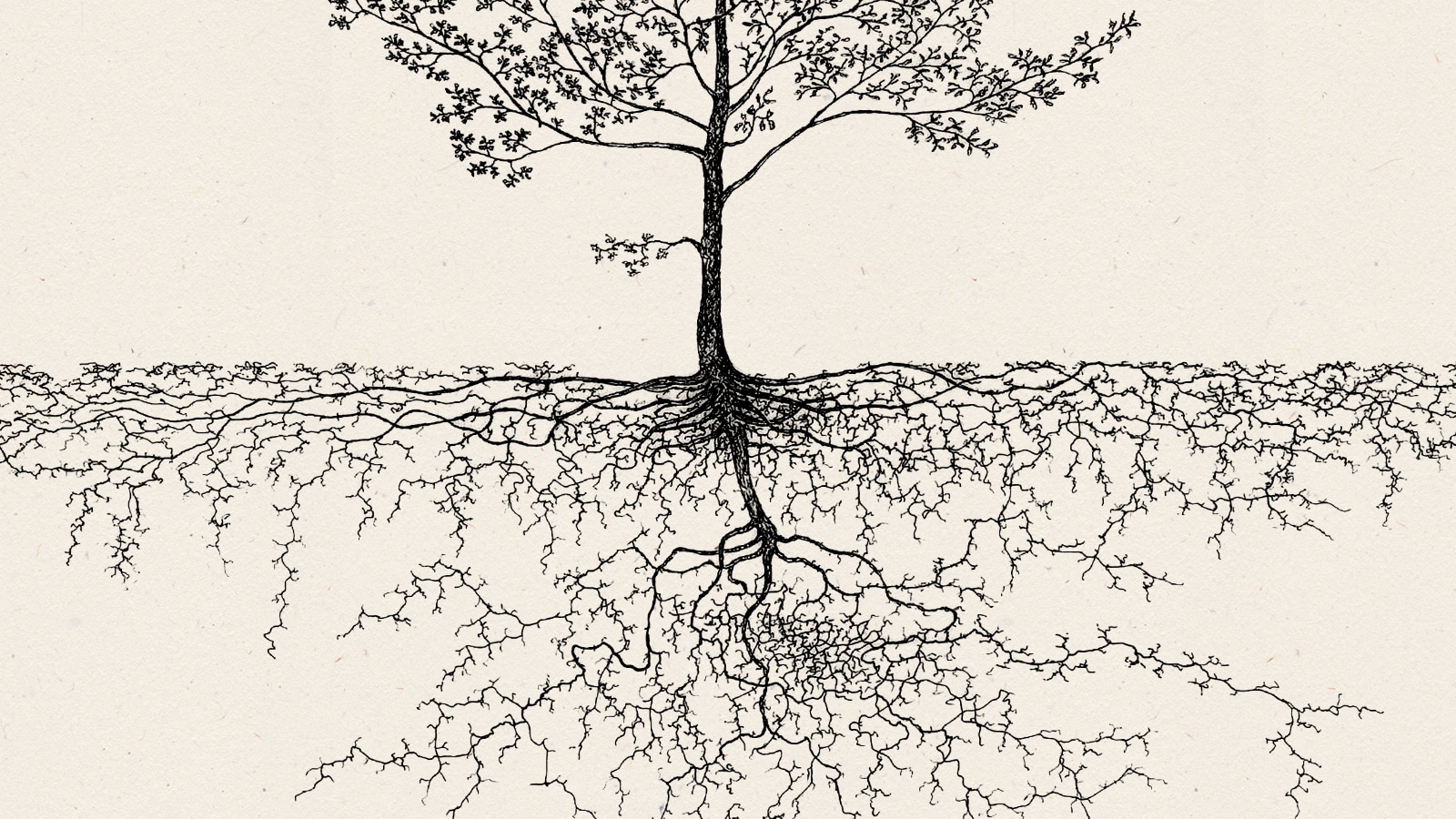

We are moving through fall this year, just a little cooler and drier than this time last year. No complaints from me, although I hope for a bit more rain in gentle, non-stormy events. Like last month, check the soil around any trees or shrubs you planted this year. Never assume surface conditions show the full story. You need to get your hands in there a few inches below the surface. This is especially important for evergreen plants like arborvitae, which rest but do not fully sleep through winter. Make sure the soil is moist before it freezes, and spread a few inches of mulch around all your trees and shrubs to help retain moisture and moderate temperature swings.

Rain Summary (from RDU):

- .79” since 10/28 (historic average 3.22”)

- 37.31” Year-to-date (historic average 39.93”)

Yard Sleuthing: A Fall Palette

I’ve been talking about leaves a lot in the last few months, and here I go again! You’d think by now humans would know everything there is to know about leaves of any color. But that bright red leaf that you stopped to pick up because of its perfect hue still has secrets.

Let’s back up and look at all the colors. Remember from grade school, leaves are green in the growing season because they contain chlorophyll. Chlorophyll absorbs red and blue light, which drives photosynthesis, and the green light is reflected.

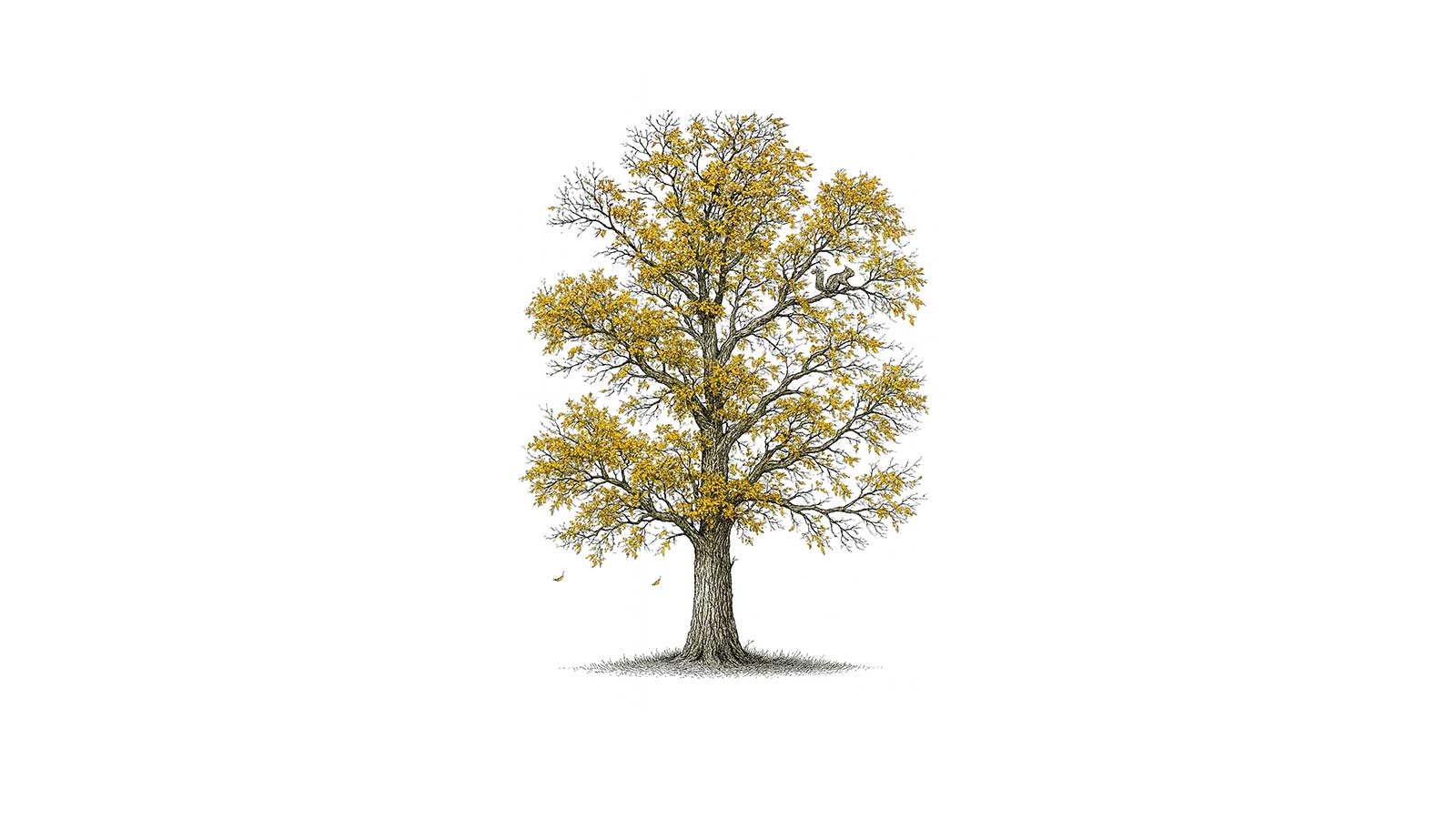

In the fall, the tree breaks down chlorophyll and pulls the valuable nitrogen from the leaves back into the stems and trunk for winter storage. The absence of chlorophyll reveals the yellow pigments in the leaves that have been there all along. Hickory leaves are bright gold in fall.

White oaks often go straight to brown because of high levels of tannins throughout their wood and leaves, which produce brown pigments. Tannins have many protective properties, including antifungal and sunscreen effects.

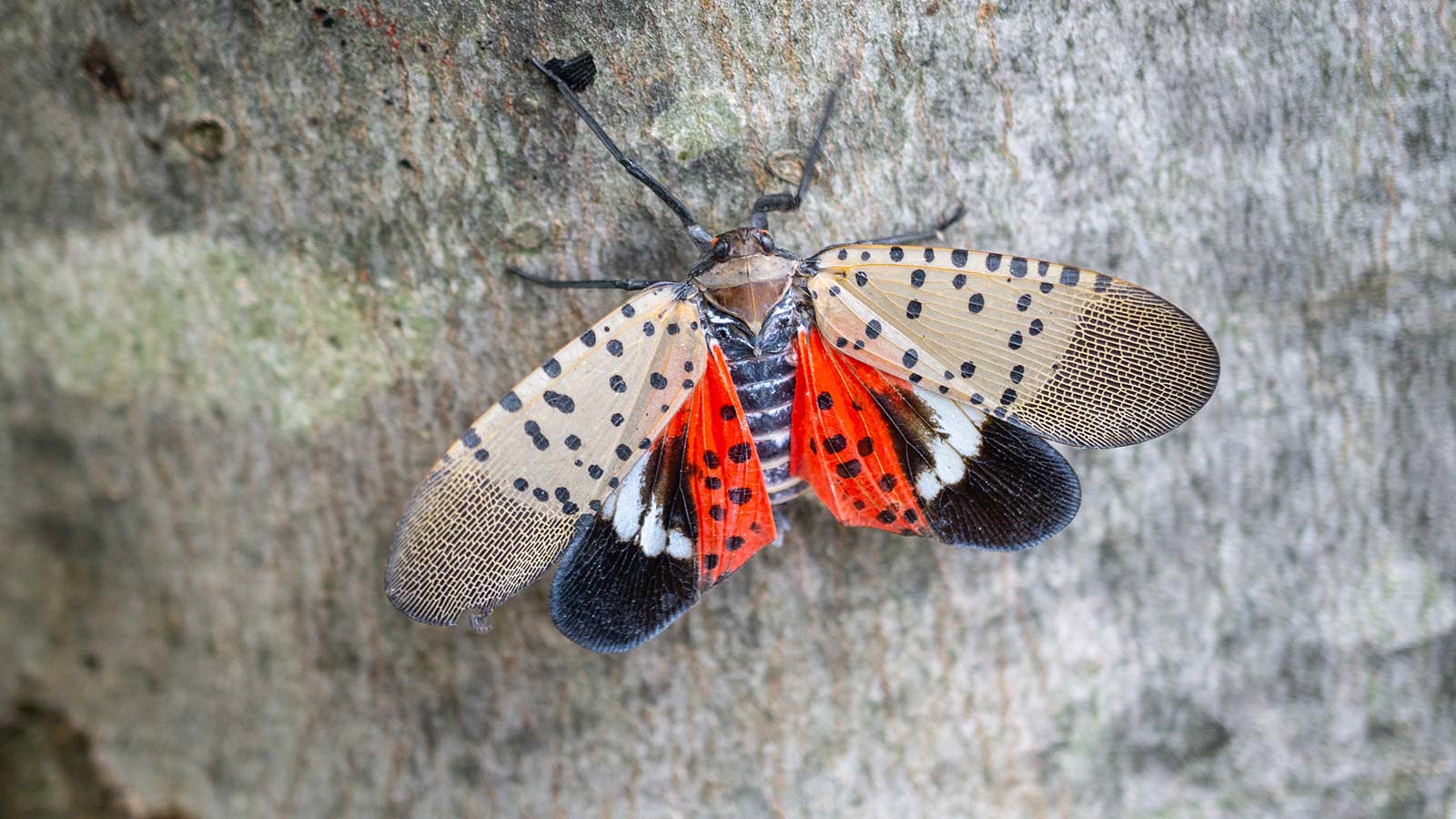

What about that red leaf? Red pigments are created in the fall, and maples and black gums famously show off their red garb. Scientists still don’t agree on exactly why trees would expend resources to make new pigments right at the end of the growing season. It’s not to please us, for sure!

There’s a lot of evidence that the red pigments act as a sunscreen, preventing solar radiation from breaking down valuable substances in the leaves the tree is storing for winter. But intriguing evidence suggests that defense against some insects, or possibly even fungicidal effects, could also be involved. It’s amazing that something as familiar as a red leaf can still hold mysteries.

Orange and burgundy shades are mixed effects, just like a paint palette.

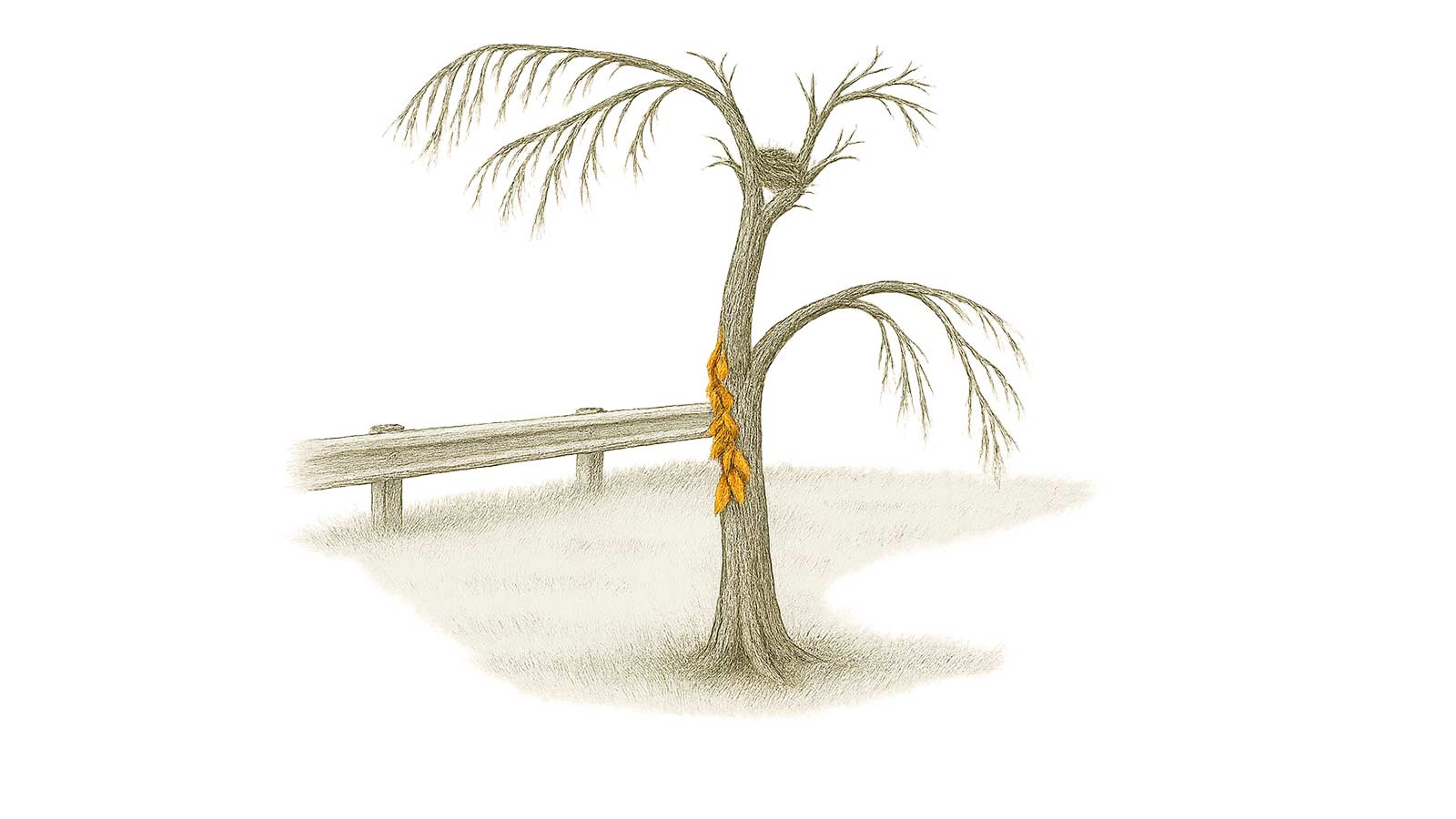

Have you ever noticed that some trees hang onto their brown leaves all through winter? Beech trees are famous for this. One of the easiest ways to spot young beech trees in the understory is during winter, when their light brown leaves hang like pendants from the delicate branches. White oaks and a few other trees sometimes do this, too. It’s called marcescence, and it’s believed to protect the tender buds from curious deer by making the twigs appear unpalatable. The dry leaves also protect against drying winter winds. Dropping dead leaves in spring also adds fresh nutrients to the leaf litter, spreading the goodness over a longer period.

Plant of the Month: Black gum or tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica)

An excellent choice for a shade tree in smaller yards. They rarely get over 50 ft tall in a landscape. One of my favorite trees, for all the reasons!

- A medium-sized to large tree of the eastern US

- Glossy green leaves that turn red or purple in fall

- Small blueberry-like fruit for birds (and making new black gum trees of course!)

- Distinctive nubby or “alligator hide” bark

- Valued for wildlife and vivid fall color

Q&A: Those Darn Deer

Q: Helen C asks: What’s wrong with the bark on one side of my little dogwood tree that I planted a few years ago? Has something been chewing on it?

A: There’s a good chance it’s deer, especially if the bark looks gouged or shredded vertically. In the fall, bucks look for small trees with a trunk from 1 to 3 inches in diameter. They start doing this in early fall to rub the velvet from their antlers, and later in the season, they begin to set up their mating territories, and tree rubs become their signposts of virility. They mark the trees with scent glands in their foreheads, exercise their neck and shoulder muscles, and leave visual clues – hopefully intimidating ones – for less dominant bucks. Don’t let special and recently planted trees become a grooming aid/gym and graffiti signpost for deer.

All you need to do is put a barrier around the trunk. I like a wire cage because I can leave it there for years if need be. You can also use a purpose-made tree guard, or a section of black corrugated plastic drainpipe sliced down one side. Anything you use as a guard should come off in the spring if it is close to the bark. A lot of damage can be done in a short period of time, so do this proactively if you can.

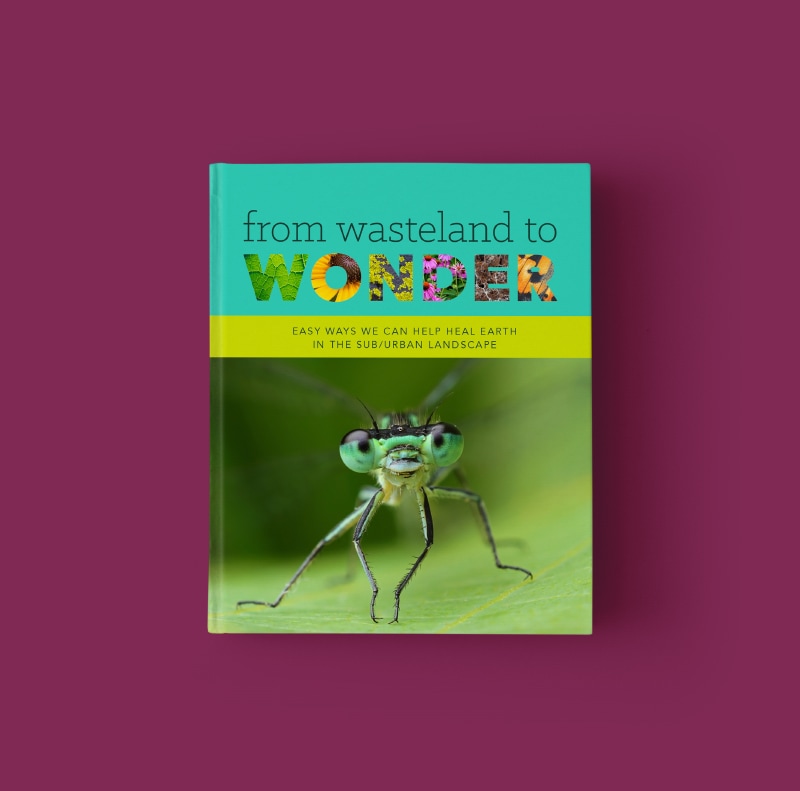

Read more about how to use wire cages to protect your trees and watch a how-to video linked on pages 77-78 in From Wasteland to Wonder.

Since I’m already discussing deer, there are a few other interesting things to know about deer and other critters that chew on your trees in winter.

Deer are browsers, rather than grazers, and like to nip the tops off your favorite blooms and the nutritious buds of your shrubs and small trees. They also greatly enjoy acorns, so if you have a lot of acorns, you might get more deer.

What about rabbits? In the growing season, rabbits are mainly grazers, endlessly nibbling grasses and other tender foliage. In winter, they switch to browsing tender buds from any tree or shrubs they can reach. You can tell whether the bud thief was a deer or a rabbit, because deer leave the twig end ragged while rabbits cut it off at a neat 45-degree angle. Rabbits might also chew bark. You will notice the little chisel marks. To protect your plants, use the same remedy: a cage similar to the one described above.

Some Things To Do Around Town Ways to have fun, learn cool stuff, make a difference and reconnect with the natural world.

- Get your kids out in Nature with the North Carolina Botanical Garden with School’s Out Camp.

- Go at least once to look for the giant trolls at Dix Park.

- Keep Durham Beautiful is organizing monthly, rotating invasive plant removal. The next one is in Lyon Park in Durham. Learn more and register on their website.

- And if you want to stay cozy and warm inside, you can listen to Basil’s first-ever live radio interview - and on Radio New Zealand nonetheless! He and host Kathryn Ryan discuss a variety of fun and interesting topics on the show Nine to Noon.

One Last Thing: Go Outside I’m (kinda) about to break my regular practice of trying to encourage you to get outside and suggest a couple of my favorite apps. There are two free and powerful resources every nature lover should have on their smartphones: Merlin and iNaturalist.

Learning about what you discover and hear on your rambles and hikes makes the experience even more meaningful. At least it does for me. I am aware of the variety of birds that visit my yard, many of which I may never know about without Merlin’s help, and I know the names of over 300 species of moths I’ve found at night because of the vast data inside iNaturalist. I will never give up my well-thumbed field guides, but these are worth it. You still might be tied to your screens, but get out there and find one new bird, and the name of some random seed pod!

Until next month, remember to sniff the blooms and listen to the birdsong.