August 2025 Treecologist Tribune

Mysterious Bumps, Lightning Strikes and Friend or Foe? 🐝

Does it seem like things are fuller and greener this year? It does to me. Probably the relentless rains. I can’t keep up with all the stiltgrass I’m tearing out from my native plantings. I have noticed that this annoying invasive grass is hiding some of my wanted treasures from exploratory deer snouts, so I’ll at least appreciate that.

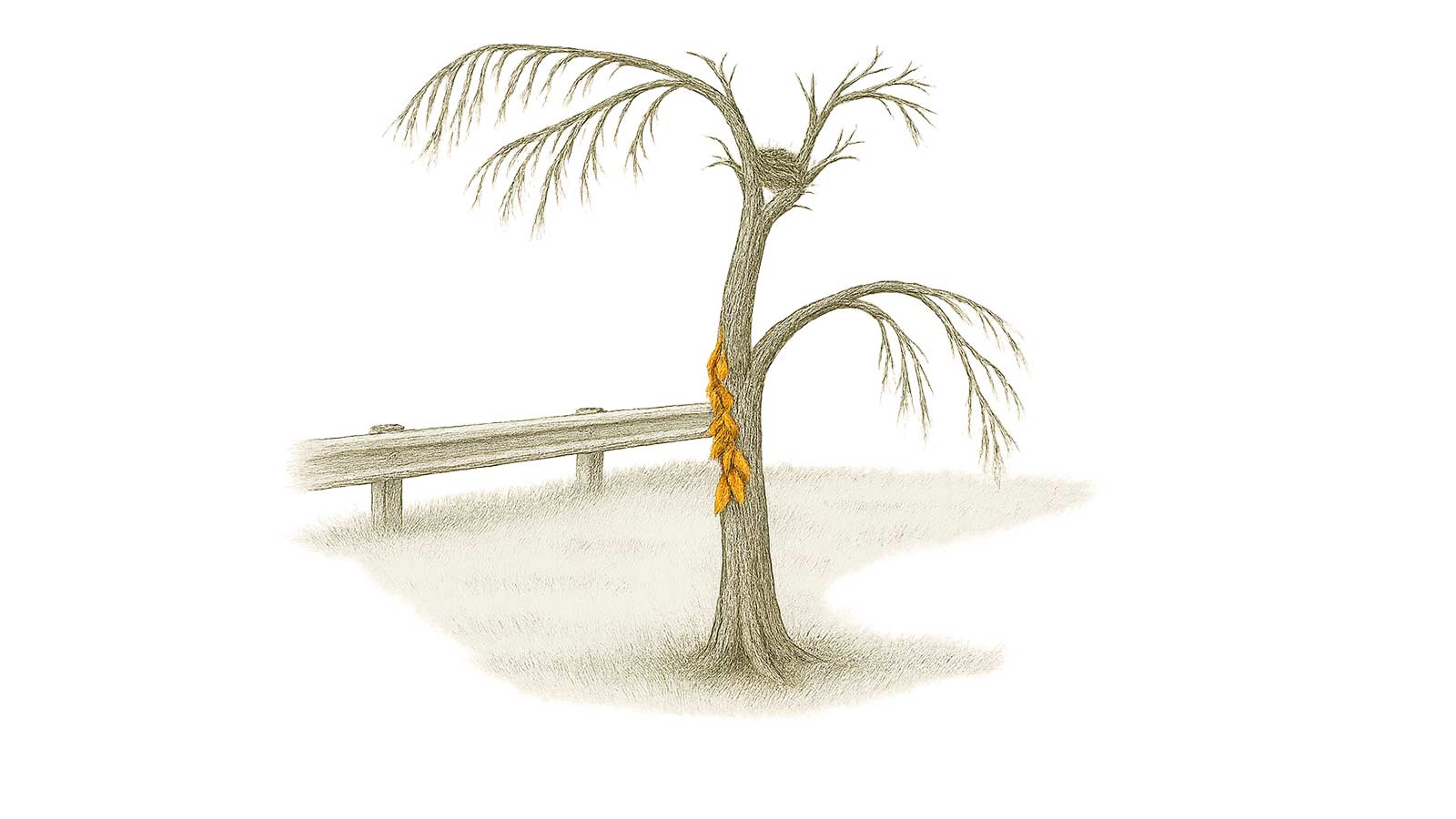

Everything is fully grown. Spiders rest big and fat in their webs. Birds are fueling up for their upcoming migration, so leave caterpillars for them instead of reaching for a spray. Shortening day length signals our trees and other plants that it is time to finish their nuts and seeds. Leaves are starting to look tired. Yellowing and weird bumps and holes are just normal signs of the give-and-take of life.

A watchful eye finds many small critters, like this little skink. By leaving the leaves and not using pesticides, I’m rewarded by these glimpses. Since the purpose of my garden is to invite all the cool critters in, I feel like I’m making progress!

Floodplains and Too Much Rain: A Look at Recent Weather Patterns

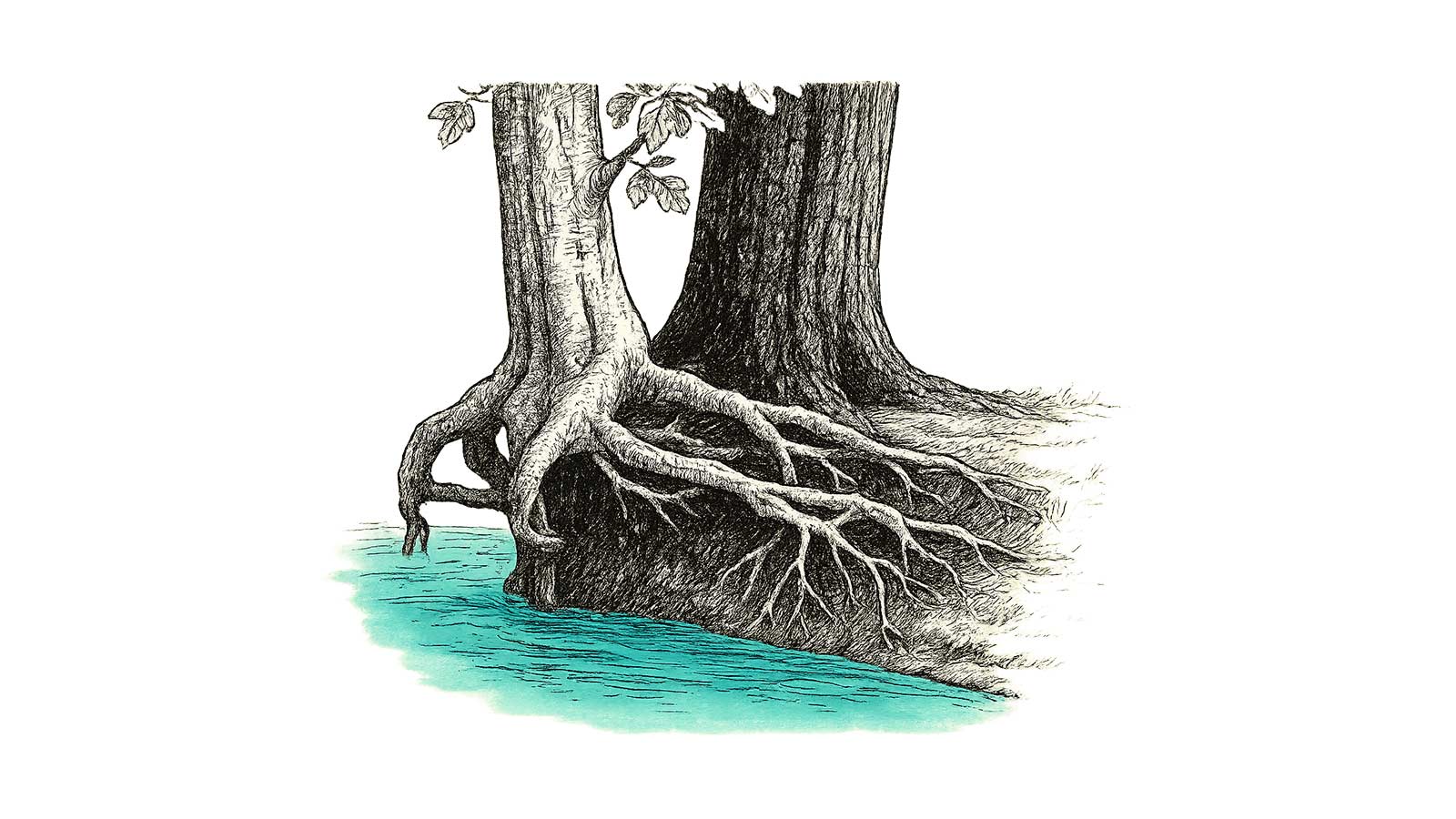

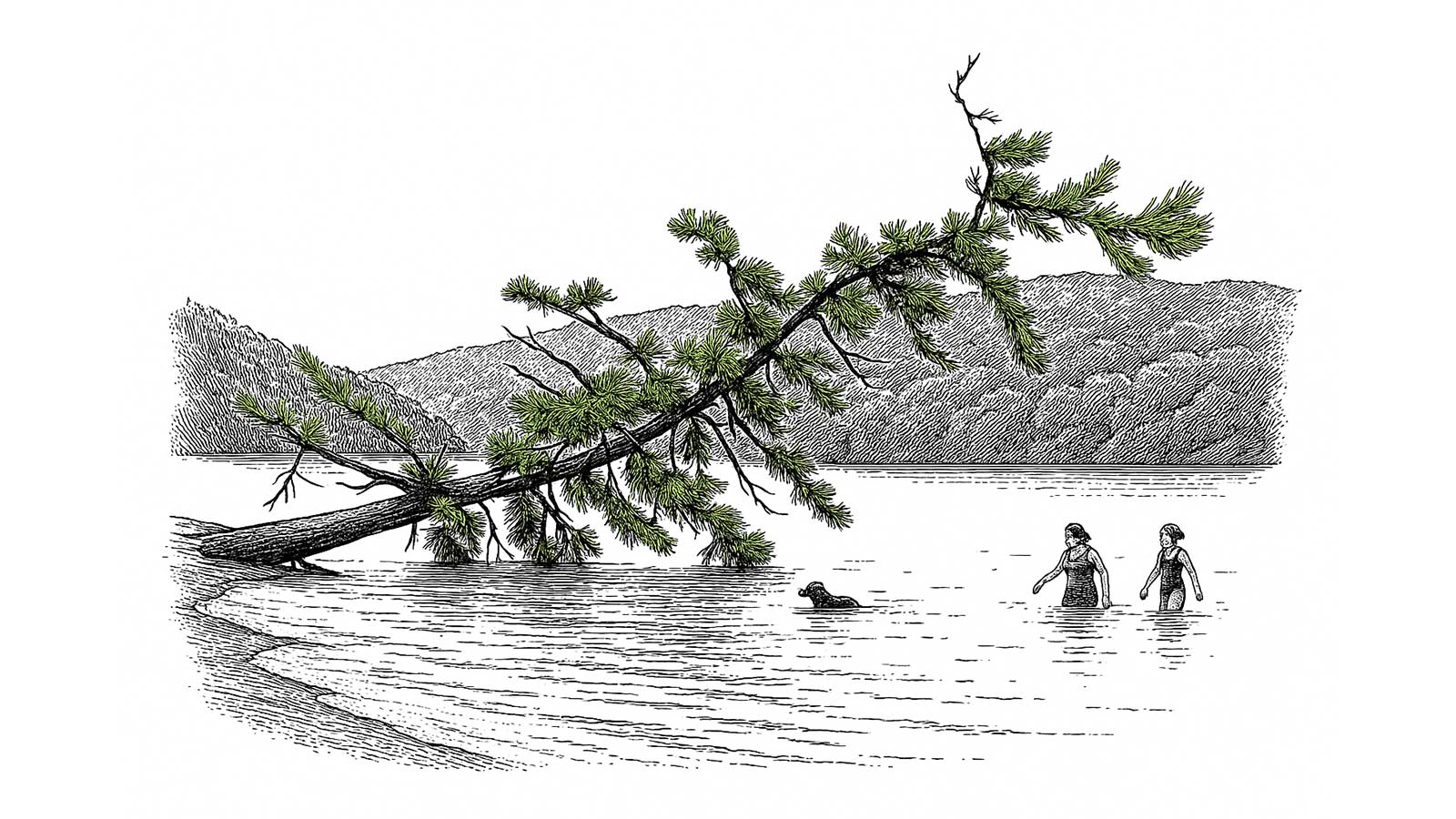

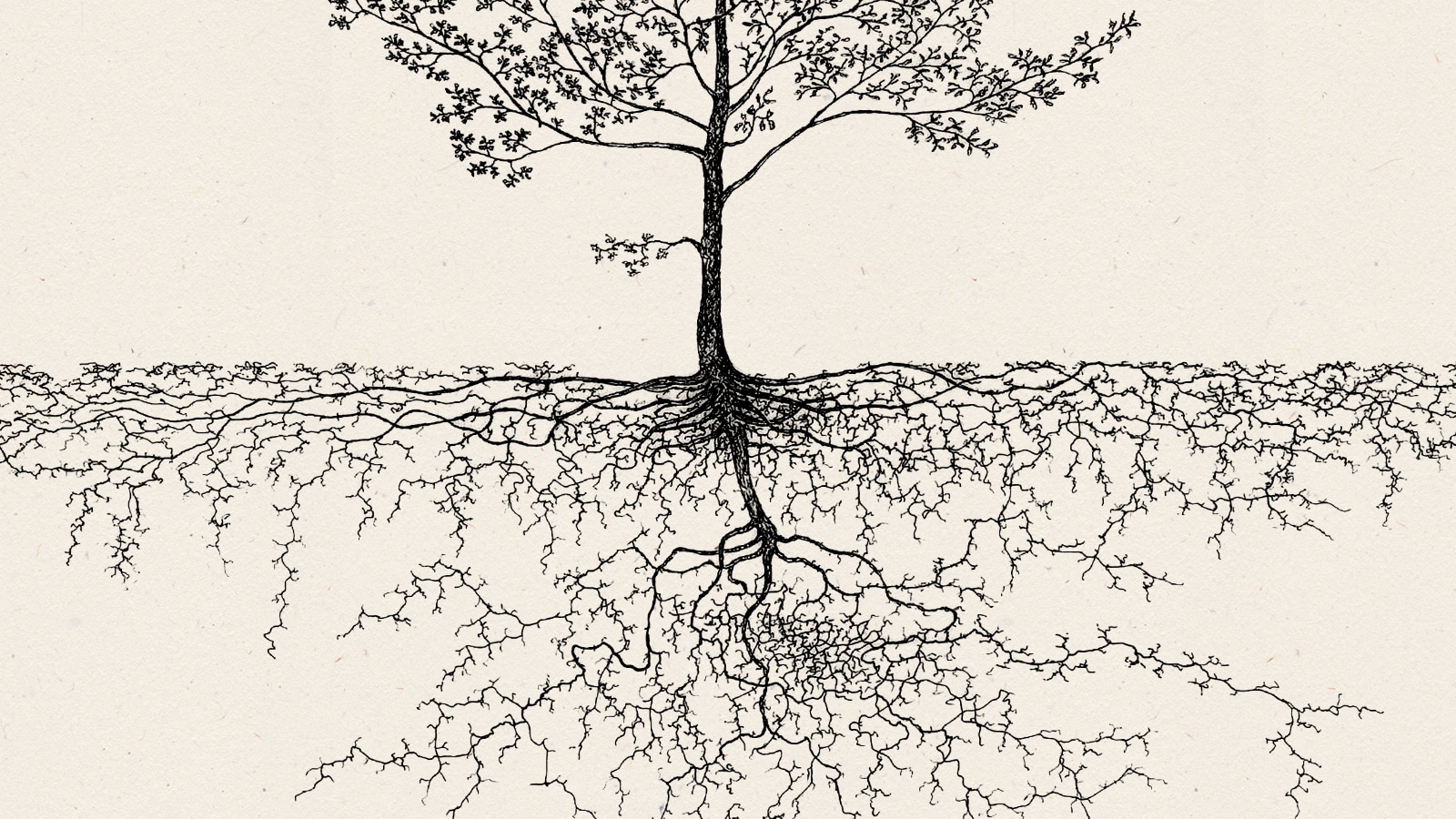

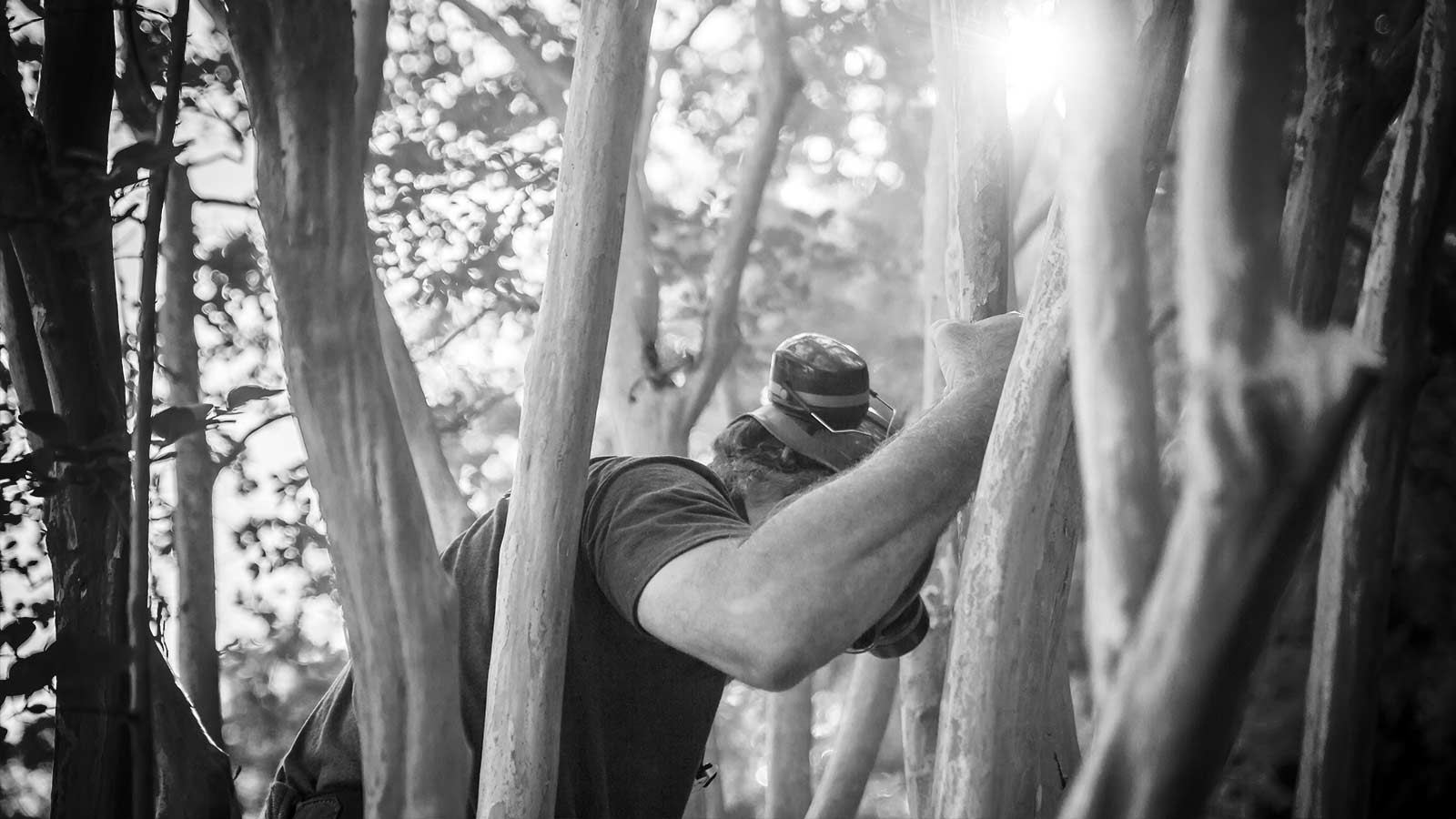

The main weather story remains rain. You hardly need me to point out that we are well above normal now. Even though the rain hasn’t come with storms since Chantal, it’s coming down in buckets. Our urban streams struggle to contain the volume. Healthy stream systems have a floodplain, and streambanks are reinforced with tree and shrub roots. During one of my recent perambulations in Little River Regional Park, the effects of the recent rains were obvious. I saw debris piles in the floodplain beside the stream and debris caught in tree limbs overhead. However, this rural stream system seemed intact. It functioned as it should. Many urban streams, however, no longer have streambanks well-woven with roots, and the floodplains meant to handle floodwaters have been developed. I believe urban stream ecology and conflicts with urban infrastructure will remain hot topics as stories of flash floods and midnight rescues continue to make news. Read Basil’s post about recent flooding in Raleigh in our new Facebook group.

🌧 Rain Summary (from RDU):

- 7.94” since 7/22 (historic average 4.81”)

- 32.69” Year-to-date (historic average 28.9”)

Garden Sleuthing

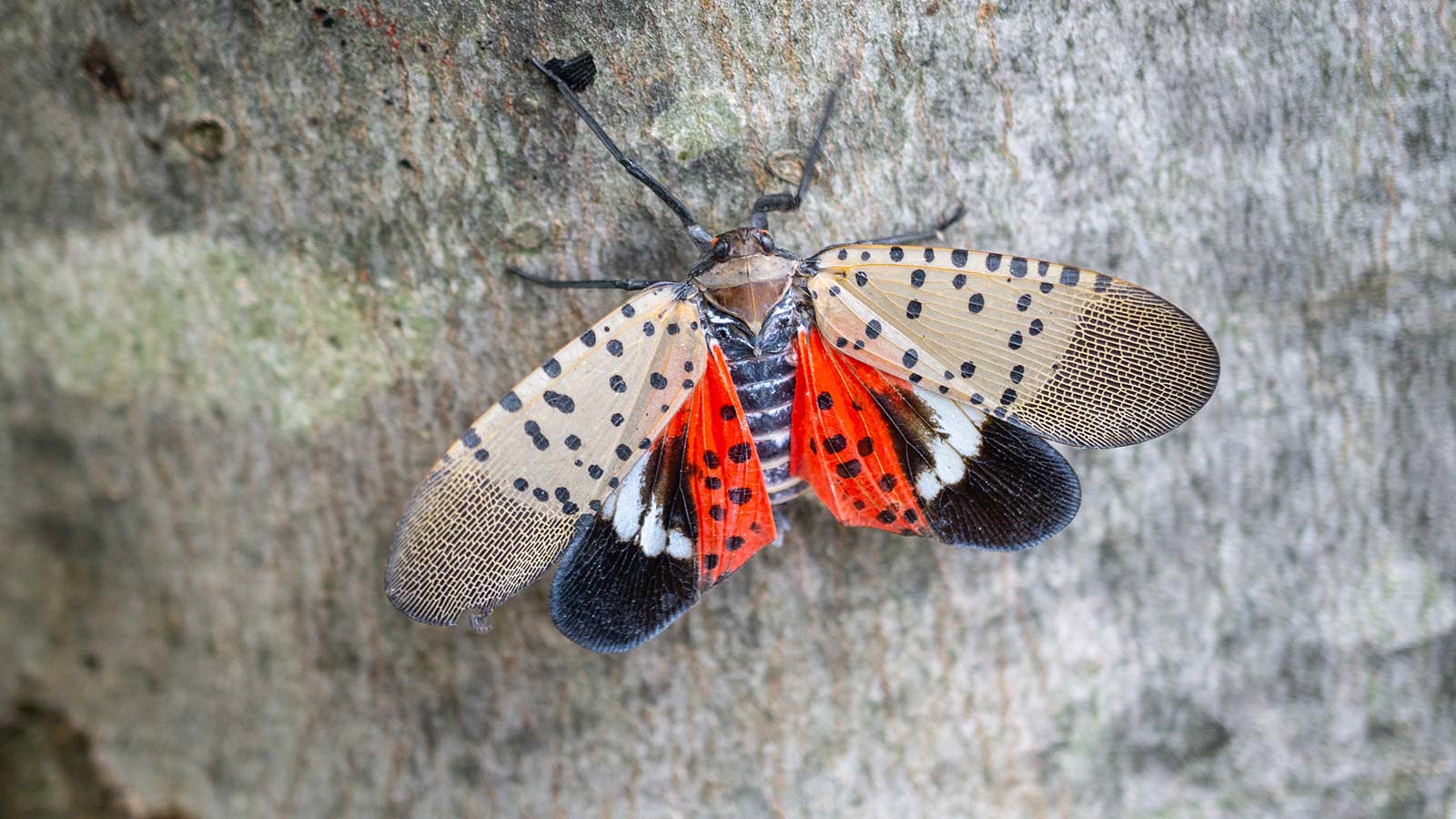

Have you ever noticed what looks like a bright red berry on a plant that doesn’t have berries, only to find out that the berry-looking thing is embedded in the leaf? What’s up with that? Bumps on leaves and stems are usually galls, which are created by specific insects on specific plants. We have tiny gall-making wasps (they don’t sting), as well as gall-making flies, aphids, and mites. Some galls resemble berries, some look like little fingers, and others are crazily ornate. Many galls are stunning to look at.

What insects do inside the plant is safely growing from egg to adult within the plant’s protection before they leave the gall to mate and restart the cycle. Like the holes in leaves, these are normal and rarely harm the host plant. Here’s a different way to think about these leaf changes – these holes and bumps aren’t flaws but are expressions of the relationships between insects and plants that have been woven by evolution over time.

Yellowjackets? Hornets? Wasps?

This is the time of year when yellowjackets and their relatives make their displeasure at our blundering near their nests pointedly obvious. Let’s identify which critters we’re talking about first, and then let’s shed some light on these misunderstood but highly valuable garden predators.

If the angry insects come swarming from underground, they are likely either the native eastern (Vespula maculifrons) or southern (V. squamosa) yellowjackets. The eastern ones are small (10-12mm) with black and yellow striping, and the southern ones are a bit bigger and usually have more orange and black striping. There’s a possibility that it could be the introduced German yellowjacket (V. germanica), although these are more likely to live in walls or buildings. But when you’re running madly away and swatting furiously, it doesn’t really matter!

If the creature you’ve annoyed is large and black and white, it’s the closely related bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata). They make large paper nests suspended from trees or other structures. Another group is the Paper wasps (Polistes sp.), which are generally more docile, but can sting, make small open paper nests with hexagonal cells that remain visible. There’s also a chance that the introduced European hornet (Vespa crabro), a true hornet, has found a nice hollow or wall to set up house in. All these species together belong in a group called the vespid wasps, and most of them live in colonies.

Wasps are both predators and pollinators. They hunt for medium-sized insect morsels like small caterpillars wherever said morsels can be found. Think of wasps as protein couriers. They bring this prey to the nest, chew it up into a tasty protein meatball for the developing wasp larvae (baby wasp). In return, the hunters are rewarded with a sweet, sugary substance from the larvae. While on patrol, the adults also satisfy their own needs by sipping nectar, making them pollinators as well.

Most vespid wasp nests are active for only one year and contain one queen along with possibly thousands of workers and larvae. In late summer, the colony is at maximum buzz, as it prepares for the final stage: producing new queens and male drones that will disperse to hopefully establish new colonies next year. They will fiercely defend their nest to ensure the entire life cycle is completed and a future is secured. The remaining wasps, including the old queen and undeveloped larvae, are doomed to die over winter. The nest is not reused. Birds and other animals feast on the remains.

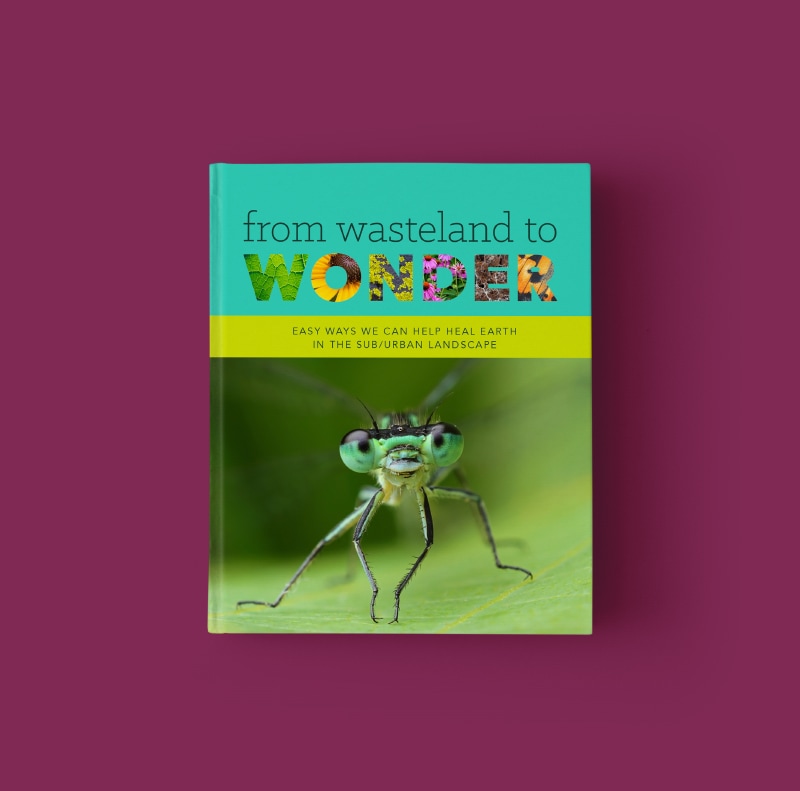

It’s interesting to notice that most gardeners love honeybees (they produce sweet honey!) but often wage war against wasps. However, our native wasps are more environmentally helpful than non-native honey bees. That’s a tough one to wrap our heads around, isn’t it? Learn more about honeybees in From Wasteland to Wonder on page 155.

It’s understandable if a nest has to be exterminated because of where it is, especially if family members are allergic to wasp venom, but if the nest can be avoided, consider marking it or putting some flagging tape around it. It’ll be gone by winter.

Q&A: When Lightning Strikes

Q: Help! I’m worried my tree was struck by lightning. Will it die?

A: Lightning is a fascinating phenomenon. Some trees that are struck by lightning are completely blown up, split apart, or catch fire and burn. No mystery there! If your tree is still standing, then carefully observing it over the coming weeks and months is key.

- Look for long vertical cracks or missing bark running down the trunk. The lightning flash heats up the water inside the tree so fast, it turns to steam and blows the bark off like a pressure cooker popping its lid.

- You might see black streaks, singed branches, or charred bark.

- Sometimes it smells like smoke even though there’s no fire.

- After the strike, the tree might start leaking sap or dripping from wounds.

- You might see strange wet marks running down the bark.

- A few weeks or months later, whole limbs might go dead, even if things looked okay at first. That’s because the strike can damage internal tissues slowly over time.

The good news is that many trees (perhaps almost half) survive a lightning strike. It depends on how much of the living tissue beneath the bark was affected. Reach out to one of our Treecologists if you suspect your tree has been struck. If it looks like all or much of the tree has survived the strike, providing it with some TLC using arborist wood chip mulch and compost tea will go a long way in helping it recover.

Read this for a fascinating story about a tree that actually thrives after being struck!

Some Things To Do Around Town

This is a bit outside of town, but if you live on the coast (or are up for a road trip), Basil is the keynote speaker at the Cape Fear Native Plant Festival on September 18th. Learn more about the speakers and vendors at the event or register for the keynote.

The third annual Cary Environmental Symposium is back. This highly anticipated event is a highlight for concerned citizens and those who like to immerse themselves in the fascinating relationships between people and everything else that co-exists with us.

One Last Thing: Go Outside

This is for the kids, and everyone who is forever young: at the park, or in the back yard, collect 10 leaves that have interesting stories drawn on them. Perhaps a big red gall, or maybe some mysterious serpentine trails, or strange dots. Use your imagination or your smartphone to figure out what happened.

Until next month, remember to sniff the blooms and listen to the birdsong.