Weathering a Hurricane: How to Stormproof Your Trees From the Ground Up

The primary ways to help your trees withstand wind, rain, and flooding.

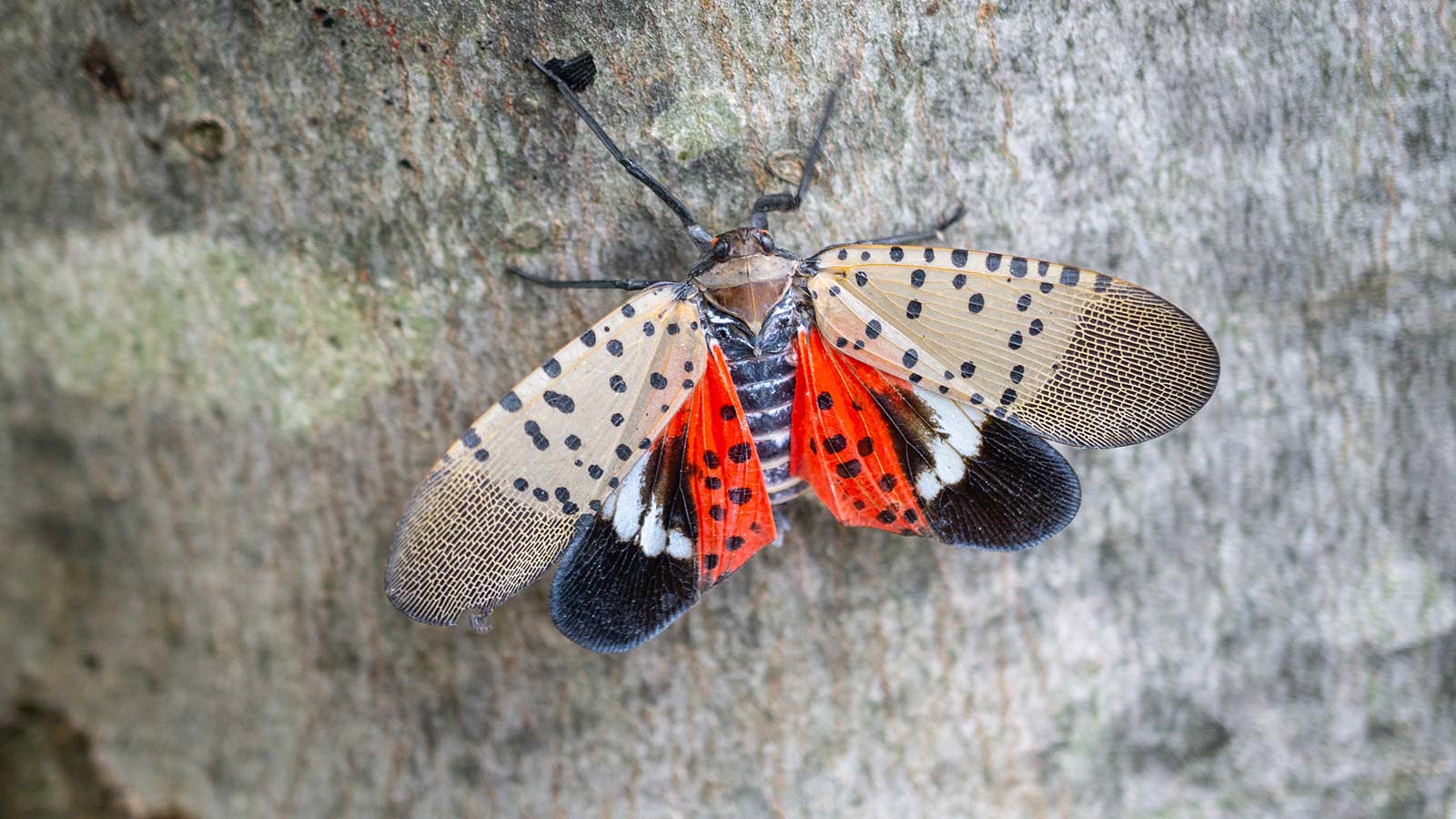

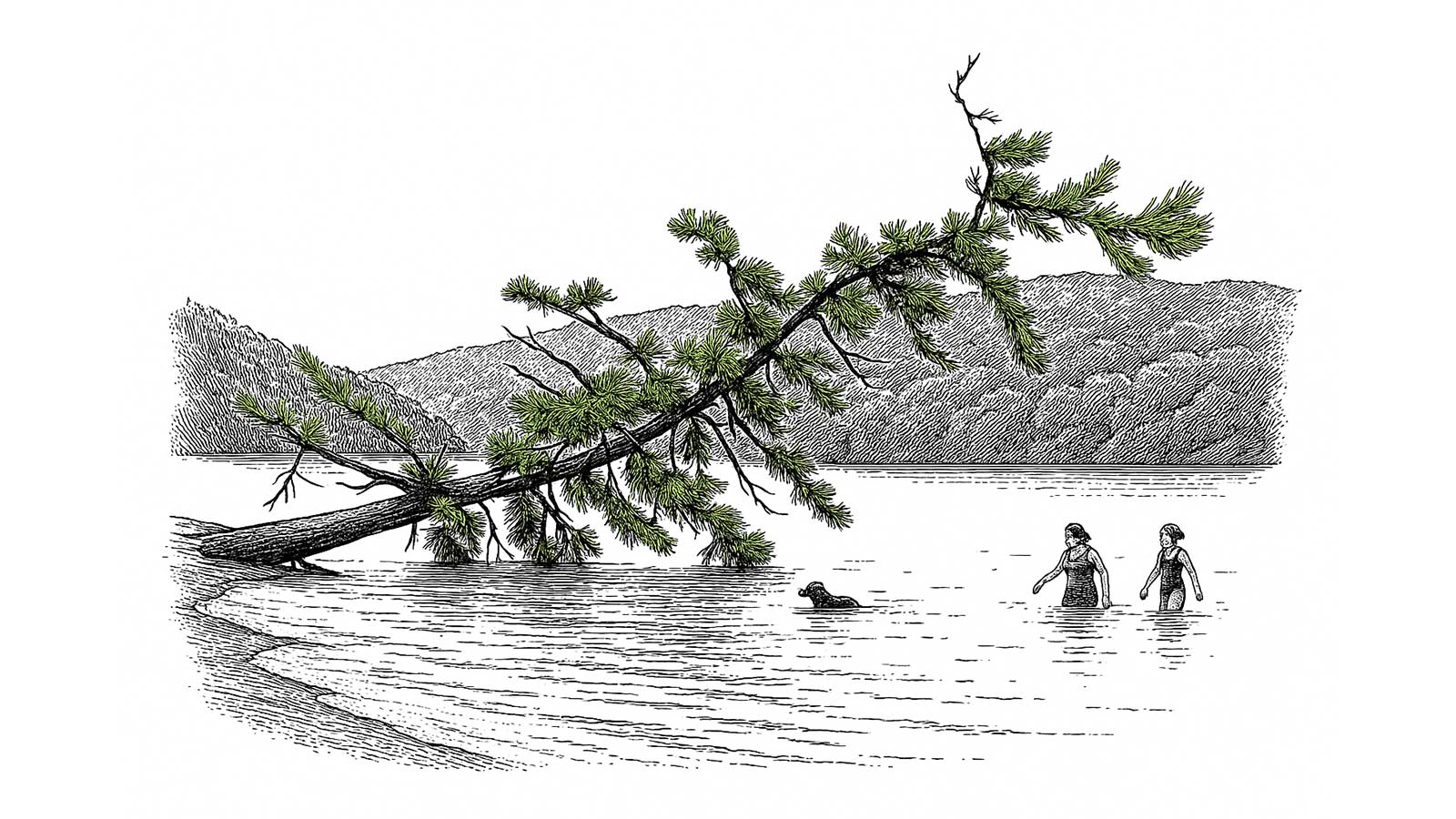

Hurricane Helene certainly hammered home the truth that hurricanes aren’t just a threat to coastal communities. Older residents of the Carolina Piedmont also remember the wrath of Hurricane Fran. Trees can snap suddenly in hurricane-force winds as they did during Helene. Water-logged, wind-whipped limbs can fail. Freight-train wind speeds can topple entire trees, especially when the soil has become oversaturated, as it did during Hurricane Fran.

News reports highlight dramatic failures and the damage hurricanes can cause when trees break or fall during storms. But what about all the trees that didn’t make the news because they didn’t fall? What is it about the trees that stood firm in the face of it? Let’s first explore how trees are resilient and then learn how we can help our trees become more resilient.

Resilient Trees

Resilient trees resemble those found in a forest. There are three pillars of resilience (physical strength and health). Resilient trees are structurally strong, their roots have not been compromised by human activity (maintaining strength), and the soil in the root zone has been allowed to develop a thriving, nutritious ecosystem, which is the main driver of good health for trees.

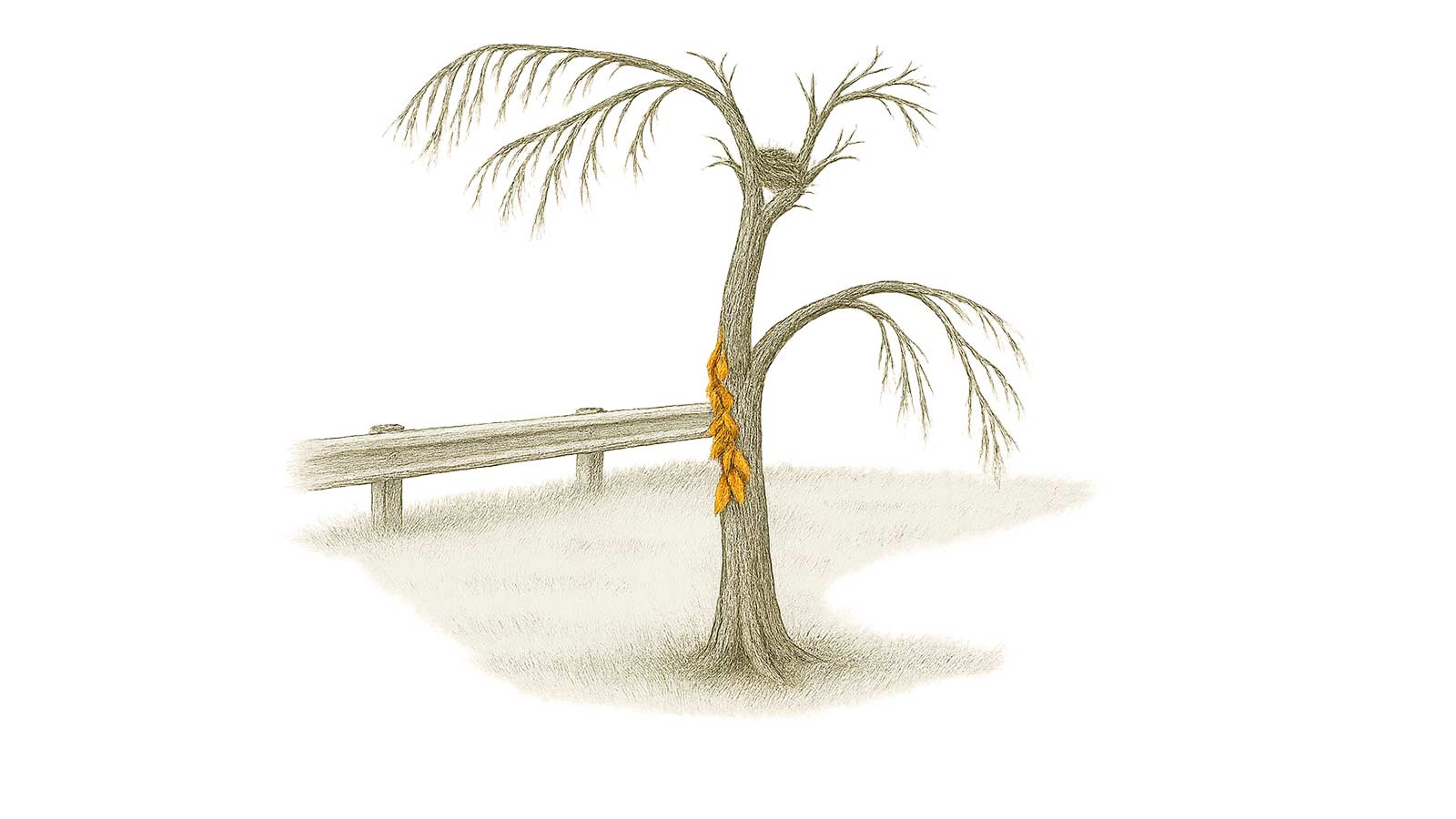

- Pillar 1: A Strong Structure Strong trees have a single, straight trunk, and the diameters of the limbs are significantly smaller than the trunk's. The limbs are held at a high angle to the trunk; that is, they are more horizontal than vertical. The base of the trunk exhibits a strong flare where the largest roots connect to it. This is called the trunk flare, and it is important that this is visible.

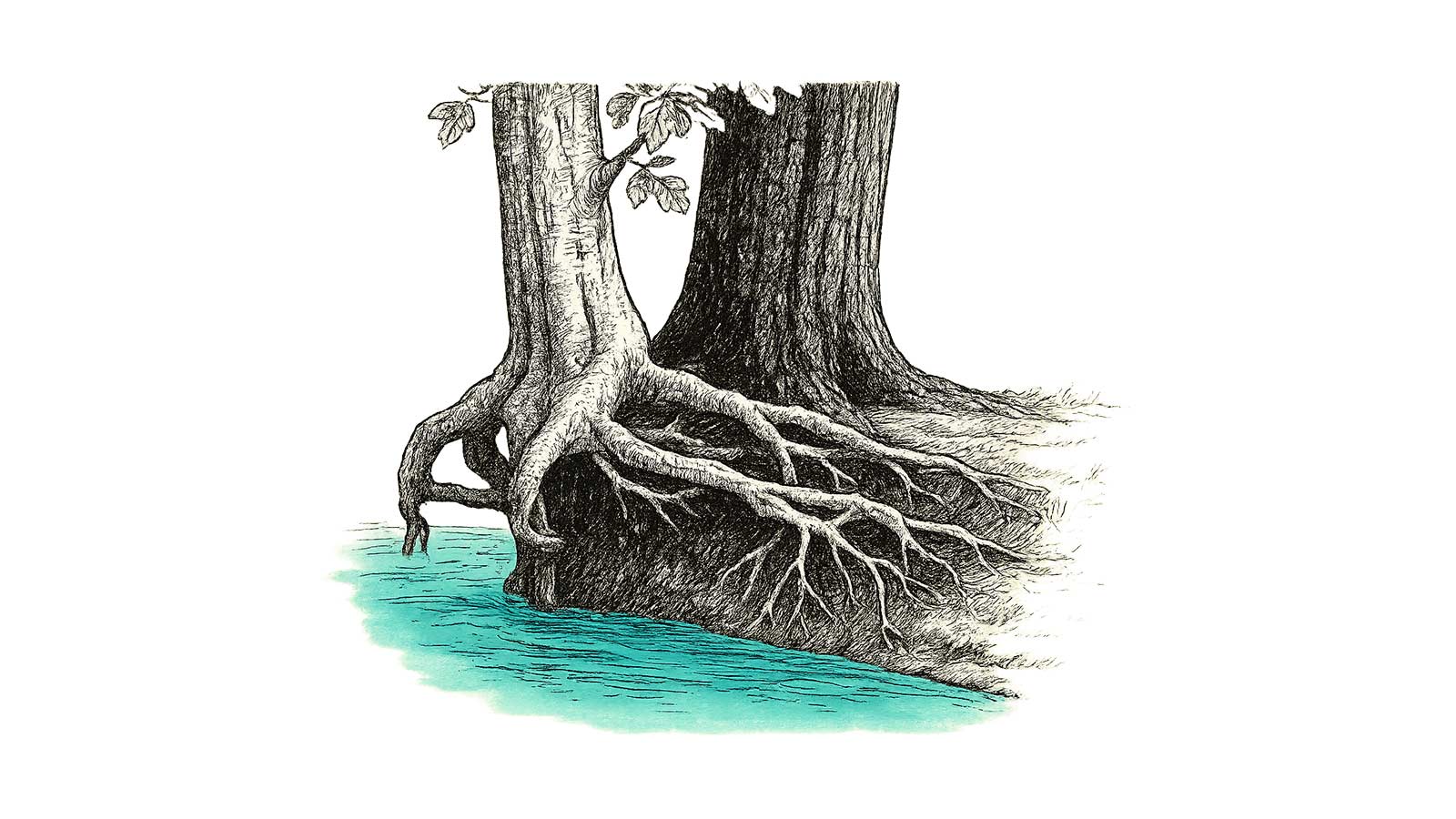

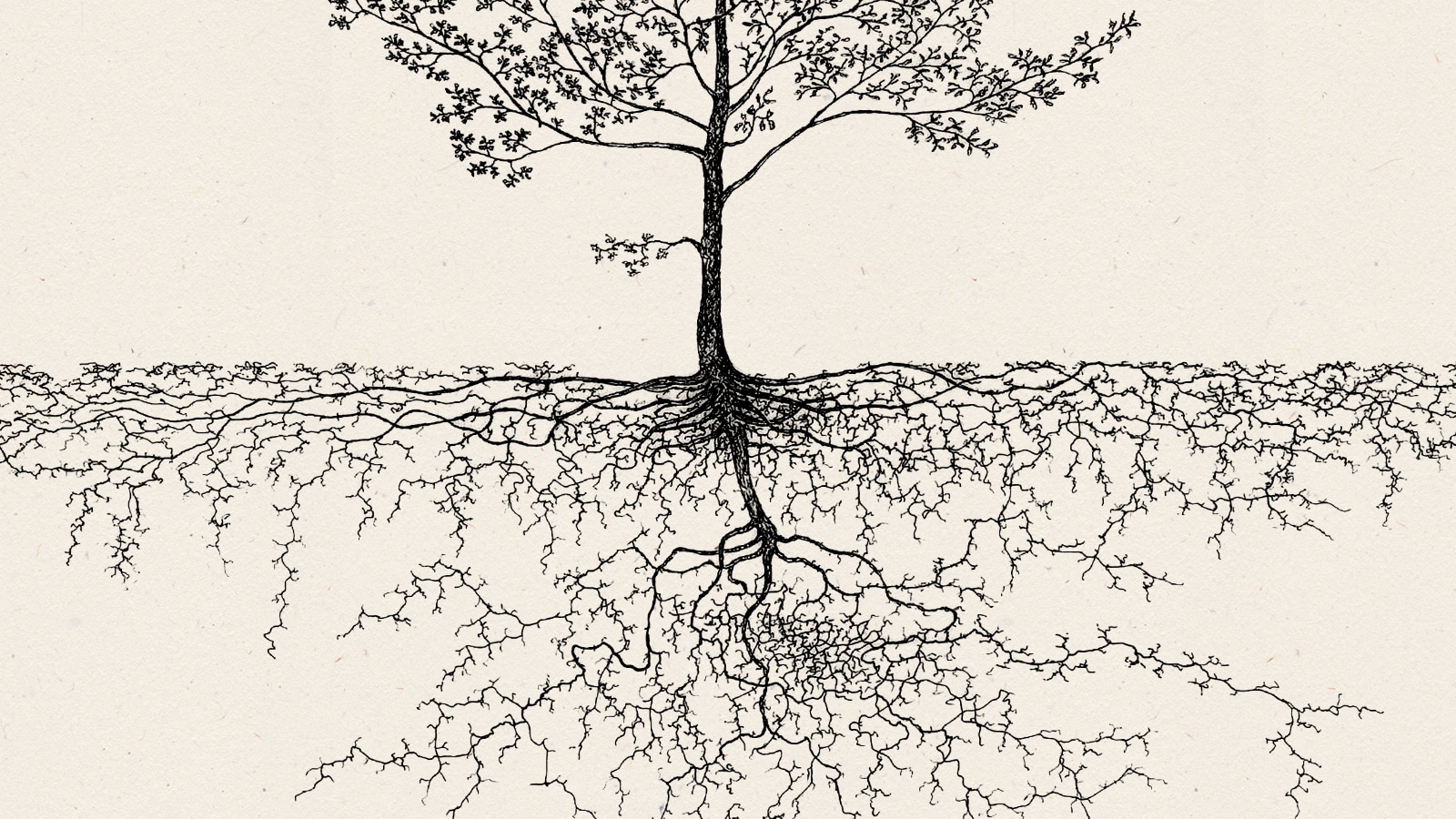

- Pillar 2: Strong Roots Maintaining strong roots is as important as maintaining the visible part of the tree. The key to strong roots is to leave them alone. Seriously! Leave. them. Alone.

- Pillar 3: Healthy Soil Healthy soil is critical for tree health. In the forest, leaves are allowed to collect and decompose, which builds good, undisturbed soil over decades and centuries.

Better Together: The Forest Community

Forest trees are not only strong individually, they are also sheltered from the full force of the wind by their neighbors. Their roots intertwine, creating an even greater foundation for stability.

We are learning that trees are not “silent"; they communicate through their roots and by releasing chemicals in soil and air that other trees can understand. They can gather resources or deploy defenses for their group. Like us, trees are stronger in a community.

Helping Our Trees Be Resilient

No one can be completely certain that their trees will not fail, and severe storms can push conditions beyond any reasonable bulwark, even in a forest. Nevertheless, there are three primary ways we can help our trees withstand adversity, based on the three pillars of resilience mentioned above. We can ensure that they are structurally sound above ground, that their roots remain uncompromised, and we can enhance tree health through improved soil care.

We want all our trees to be strong and healthy, but it’s most important to ensure that trees capable of striking a target like a house, either by branches breaking off or the entire tree failing, receive our attention and maintenance. Trees far away in natural areas can be left alone to do what trees have always done: die and fail in their own time, providing homes for woodpeckers and other creatures while they slowly return to the earth.

Solution 1: Pruning for Strength

Thoughtful structural pruning is the best way to correct canopy conditions that result in weakened tree structure. This type of pruning addresses these weaknesses by removing all or part of the defect and directing future growth more appropriately.

If some of your tree’s limbs are nearly vertical, this may indicate co-dominant trunks rather than branches. Additionally, co-dominant trunks often have similar diameters. These trunks compete with one another and are not as securely attached as a proper branch. This is a common point of failure, which can be addressed by removing or, more typically, reducing one of the trunks.

Another weakness, particularly in trees grown in the open without the support of forest trees, is overextended limbs. Trees attempt to strengthen themselves to withstand typical living conditions, but they don’t consider redundancies as a structural engineer would for a bridge. They can cope with limb loss, but that lost limb might crush your car. Over-extended limbs can often be shortened back to an appropriate growing point.

Check out the fundamentals of structural pruning to learn more about how this is done. A warning: Structural pruning is not topping, an outdated practice that fails to address tree health or strength. Do not let anyone persuade you to make your trees “safer” this way.

When is the ideal time for structural pruning? When the trees are small, before significant structural weaknesses arise. The worst time? The day before a storm approaches. The second-best time is now.

Another option that can be used in conjunction with pruning is cabling or bracing, especially for very large trees where significant pruning opportunities may no longer be safe for the tree’s health.

Solution 2: Leaving the Roots Alone

Even though they are beneath the soil (and we hope to never actually see them) roots are an essential part of the tree. Depending on the species and the qualities of the soil, the roots extend a few feet underground. If they have enough space, the roots will stretch well beyond the canopy.

The two primary ways we compromise root strength are by raising the grade, which buries the trunk flare, or by cutting roots to make room for construction. These interferences can weaken a tree enough to cause a decline in health or even to physically destabilize it.

If planned construction encroaches beneath the canopy spread of your tree, consider creating a protection plan and implementing it before construction begins. Fencing and a deep mulch blanket are just two of the methods that can be employed to help protect trees. Call a qualified arborist to assess the impact and help devise your plan.

Solution 3: Soil Improvement

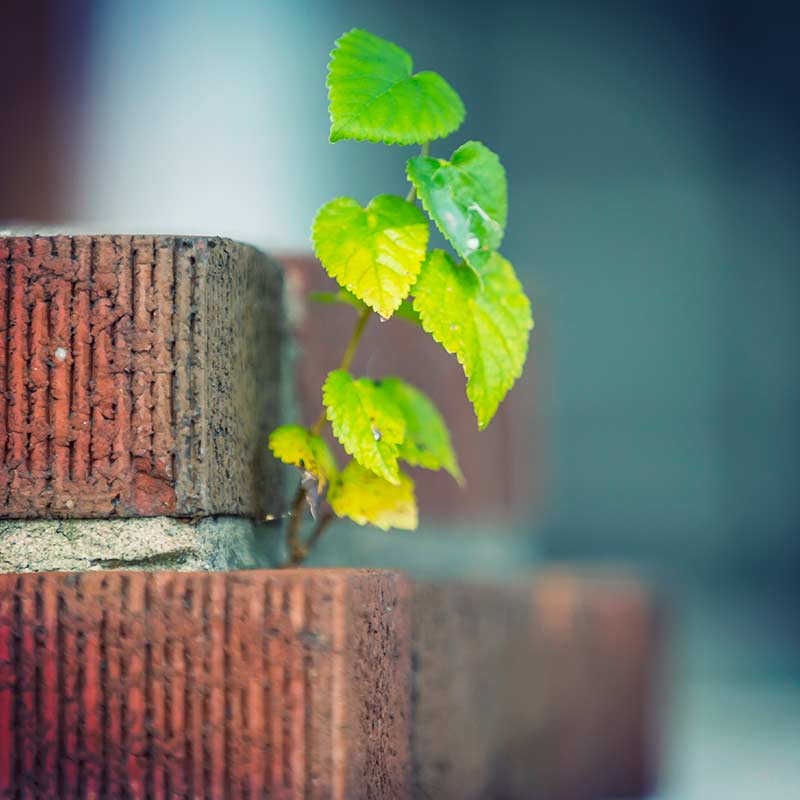

Suburban soils are much more impoverished than forest soils, to the point that very little of what is considered good soil remains. Suburban soils lack nutritional value due to insufficient organic material. The seasonal addition of salt-based chemical fertilizers is another setback, as it harms rather than helps soil health. Soil compaction, primarily caused by human activity, is another significant issue affecting soils in areas where humans live and work.

The least we can do is leave the leaves in autumn, but we can do even more. We can correct decades of soil degradation by aerating and enriching it with compost, then topping it off with 3 or 4 inches of biodegradable mulch. Spreading arborist wood chips beneath as much of the canopy as you can is one of the best ways to protect roots and improve soil. But don’t pile it up against the trunk into a mulch volcano! Here we explain what that is and why they should be avoided.

Plant understory shrubs or herbaceous plants beneath the canopy. This enhances wildlife benefits, reduces compaction because you’re not walking on it, and minimizes mower damage since you’re not mowing.

What About Leaning Trees?

It’s quite reasonable to cast a suspicious eye at a tree leaning toward your house. The good news is that the leaning tree might be perfectly healthy. Trees at the edge of a group often grow toward sunlight rather than straight up.

Ask some questions. Has the tree always leaned, is that a new development, or has the lean increased? Does the soil appear disturbed on the far side of the lean near the trunk? Are there roots beginning to show? Those are not good signs, and, whether a hurricane is coming or not, it is a candidate for assessment. Give us a call if a leaning tree concerns you.

Watching Your Trees

Just like us, trees show the effects of age. Wounds, rot, cracks, and other defects can take a toll on old trees. But such badges of life are not necessarily signs that a tree will fail. For example, hollowness isn’t necessarily a major flaw; hollow trees can exhibit remarkable strength. In fact, when they become very large, it is one of the ways trees preserve strength. Cavities greater than one-third of the tree's circumference warrant a professional assessment.

Like us, trees thrive better in community (a forest!) rather than alone. Trees that are isolated after development for a new home or those at the edge of the remaining forest are especially vulnerable to being uprooted in storm conditions for two reasons: Their roots and soil have likely been compromised by construction, and they are exposed to conditions to which they have not adapted. Whenever possible, keep your trees in groups. Whether removing trees for development or planning a new landscape, grouping trees enhances the resilience of all trees.

Sometimes, it’s hard to know whether a tree is safe. How much is too much, and how bad is very bad? Make it a regular practice to observe your trees from the canopy to the root zone. Look for changes, including limb dieback, trunk defect changes, fungal growths, and changes in lean. If you spot weaknesses, give us a call or send us an email. We can provide your trees with a prescription for resilience and the strength to weather hurricanes.